When Facebook Isn’t Forever: Why Local History Needs a Home You Control

Summary: Social media has become the default place where communities share their history, but it was never designed to preserve it. From lost early 2000s photos to comments and context disappearing over time, this article explores why Facebook isn’t a reliable home for local history and how libraries and historical societies can create a digital space they truly control.

For more than a decade, social media has quietly become the default place where communities store their memories.

Local events are photographed and posted to Facebook. Old images are shared in nostalgia groups. Milestones, celebrations and everyday moments live on timelines, feeds and comment threads. It feels convenient. It feels visible. It feels permanent.

But it isn’t.

For libraries, local history groups and historical societies, this creates a growing risk: an increasing proportion of community history exists only on platforms you don’t own, don’t control, and can’t preserve properly.

If history matters, it needs a home built to last.

The illusion of permanence

Social media gives the impression of stability. Photos resurface in “On This Day” reminders. Old posts attract new comments. Community groups grow into thousands of members.

But these platforms were never designed to be archives.

They prioritise engagement, not preservation. Visibility, not context. Speed, not longevity.

Content can be:

Deleted by users

Lost when accounts are closed

Buried by algorithms

Compressed or stripped of metadata

Removed entirely if a platform changes policy, ownership or business model

The most striking reminder of this fragility came in 2019. Myspace confirmed that a server migration error resulted in the permanent loss of all content uploaded to the platform before 2016, roughly 12 years’ worth of photos, videos and audio files with no backups available. The site’s own notice warned that “any photos, videos, and audio files you uploaded more than three years ago may no longer be available …,” leaving millions of user-generated memories inaccessible.

An entire chapter of digital cultural memory simply vanished.

Facebook and other platforms may feel more stable today, but the underlying issue remains the same: they are not accountable to communities as long-term custodians of history.

The early 2000s memory gap (and why it matters now)

This risk is not theoretical. We are already living with the consequences.

The early 2000s represent one of the most vulnerable periods in modern memory-keeping. It was the first era of mass digital photography, but long before reliable cloud storage, clear standards or preservation awareness existed.

A recent BBC article, Why your early 2000s photos are probably lost forever, explains how an entire generation of images disappeared across broken laptops, obsolete devices, CDs, memory cards and defunct online services.

What felt like abundance was actually fragility.

For community archives, this has created a strange imbalance:

Strong coverage of the 1950s–1990s

A noticeable dip between roughly 2000 and 2010

A resurgence again in the smartphone era

This gap is not because nothing happened. It’s because no one was responsible for keeping it safe.

Why libraries and local history groups are uniquely affected

Unlike large national institutions, local heritage organisations often rely on:

Community donations

Volunteer-led collecting

Informal sharing and discovery

When photos and stories live primarily on Facebook:

They are harder to accession

They arrive without structure or metadata

They lack consent clarity

They are difficult to search, preserve or reuse

They disappear when individuals disengage

Over time, this creates a silent erosion of local memory.

The danger is not just losing images, but losing context:

Who is in the photo?

Where was it taken?

Why did it matter?

What does it say about everyday life at that moment?

Without that context, history becomes thinner and less meaningful.

The real value of Facebook (and the hidden risk)

It’s important to acknowledge why Facebook feels so powerful for local history.

People don’t just post photos.

They comment on them.

They identify faces.

They correct dates.

They share anecdotes.

They add names, relationships and local knowledge that never existed in the original image.

In many cases, the comments become more valuable than the photo itself.

But this is where the hidden risk lies.

On Facebook, that context lives separately from the original file.

The image is a compressed copy.

The names and stories exist only as comments in a thread.

If the post is deleted, the group closes, the account disappears or the platform changes, that context is lost.

Even when images are downloaded later, the meaning stays behind.

From an archival perspective, this is one of the biggest problems with relying on social platforms for memory-keeping: conversation and content are divorced from one another.

Preserving conversation with the record

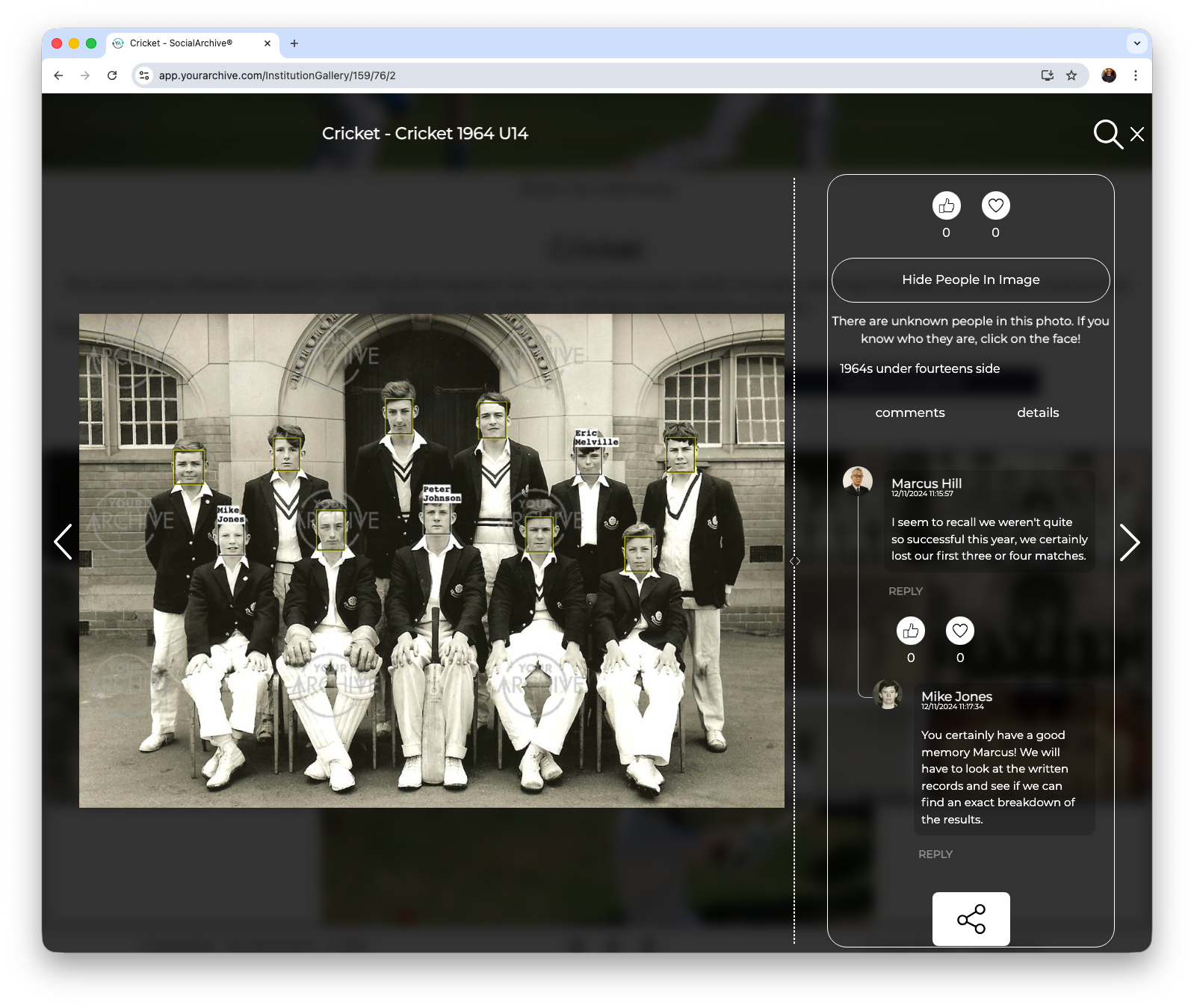

An example of a photo within YourArchive showing people data and commentary alongside the image stored in the digital archive.

A purpose-built digital archive treats conversation differently.

On a platform like YourArchive, contributors can still:

Comment on images

Identify people

Add memories, corrections and explanations

Build collective understanding over time

But crucially, that context is:

Stored alongside the original file

Retained as part of the record

Searchable and preservable

Available to future users, not just today’s audience

The photograph and the story remain connected.

When someone identifies a face, explains a tradition or adds a personal memory, that insight becomes part of the historical record and not a fleeting interaction tied to a single post.

For libraries and local history groups, this is the difference between:

A lively conversation that eventually disappears

andA meaningful contribution that endures

The early 2000s problem is still solvable (for now)

One of the most important insights from the early 2000s memory gap is this:

We still have a window of opportunity.

The people who lived through that period are now in their late 30s, 40s and early 50s. Many are:

Helping parents downsize

Discovering old CDs, DVDs and memory cards

Reflecting on identity, place and belonging

Willing to share stories, even if photos are missing

This means preservation does not have to rely on images alone.

If photos are gone, people can still contribute:

Audio memories

Short video reflections

Written stories

Descriptions of places, traditions and relationships

These first-person accounts often carry more historical value than images alone, because they explain meaning, not just appearance.

From passive sharing to intentional collecting

One of the biggest shifts libraries and local history groups can make is moving from passive observation to intentional collecting.

Instead of hoping important posts surface on social media, institutions can:

Run focused memory campaigns

Set clear timeframes (for example, “Life in our town, 2000–2010”)

Use simple prompts

Offer multiple ways to contribute

Capture stories while context still exists

Small contributions, gathered at scale, create a powerful collective record.

This approach mirrors ideas explored in The Early 2000s Memory Gap: Why Schools and Universities Need to Collect These Stories Now. While written for education, the principle applies just as strongly to community history: transitional digital periods require deliberate action, not passive reliance on platforms.

Share widely. Preserve centrally.

None of this means abandoning Facebook.

Social platforms are valuable for visibility, discovery and participation. They are often where communities already are, and where engagement happens most naturally.

The key is intent.

By all means:

Share archive content to Facebook

Encourage discussion and identification

Invite people to engage where they feel comfortable

But always drive that engagement back to a space you control.

When the original file, contribution form or full story lives in your own digital archive:

You keep the master record

You preserve the context

You retain consent and provenance

You ensure the history survives beyond the platform

Facebook becomes a doorway, not the destination.

Beyond preservation: belonging and participation

There is also a human dimension to this shift.

When communities are invited to contribute intentionally:

People feel recognised

Stories become shared, not scattered

Memory builds belonging

Archives reflect lived experience, not just official narratives

For libraries and local history groups, this strengthens relevance in the present, not just the past.

Preservation becomes something people participate in, not something hidden behind the scenes.

The choice facing local history today

Every archive has gaps. That’s inevitable.

But the early 2000s gap is one we can still address if action is taken now.

The bigger question is this:

Will future historians find community life preserved in structured, searchable archives… or fragmented across abandoned platforms, broken links and lost accounts?

Facebook isn’t forever.

History deserves better than borrowed space.

It deserves a home you control.

If you’d like to create a digital home for your community’s history (one you control, preserve and can share with confidence), we’d love to help.

Get in touch to learn more about YourArchive, or book a demo to see how it works in practice.

FAQs:

Is Facebook a reliable place to store historical photos long term?

Facebook is not designed to be a long-term archive. While it makes photos easy to share and discuss, it compresses files, strips metadata and separates images from their historical context. Content can also be deleted, buried by algorithms or lost if accounts, groups or platforms change. For long-term preservation, communities need a dedicated digital archive they control.

Why isn’t social media suitable for preserving local history?

Social media platforms prioritise engagement, not preservation. They are built for speed, visibility and interaction, rather than long-term stewardship. Historical records require stable storage, retained metadata, clear provenance and continuity beyond individual users, which social platforms are not designed to provide.

What happens to comments and identifications on Facebook over time?

On Facebook, comments that identify people, places or events exist separately from the original image. If a post is deleted, a group closes or an account disappears, that context is lost. Even if an image is later downloaded, the historical meaning contained in the comments does not come with it.

What is the early 2000s digital memory gap?

The early 2000s digital memory gap refers to a period where large volumes of photos and digital content were created but poorly preserved. Files were stored on fragile devices, obsolete formats and early online platforms that later shut down. As a result, many photos and stories from roughly 2000–2010 are now missing from personal and institutional archives.

How can libraries and historical societies preserve community memories properly?

Libraries and historical societies can preserve community memories by collecting original files into a central digital archive, capturing stories alongside images, retaining metadata and encouraging contributions through structured campaigns. Social media can still be used for outreach, but preservation should happen in a system designed for long-term access and control.

Can communities still use Facebook if they have a digital archive?

Yes. Facebook works well as a discovery and engagement tool. Communities can share archive content to social media to encourage participation and conversation, while directing people back to a central archive where original files and context are preserved together. In this model, social media acts as a doorway, not the destination.